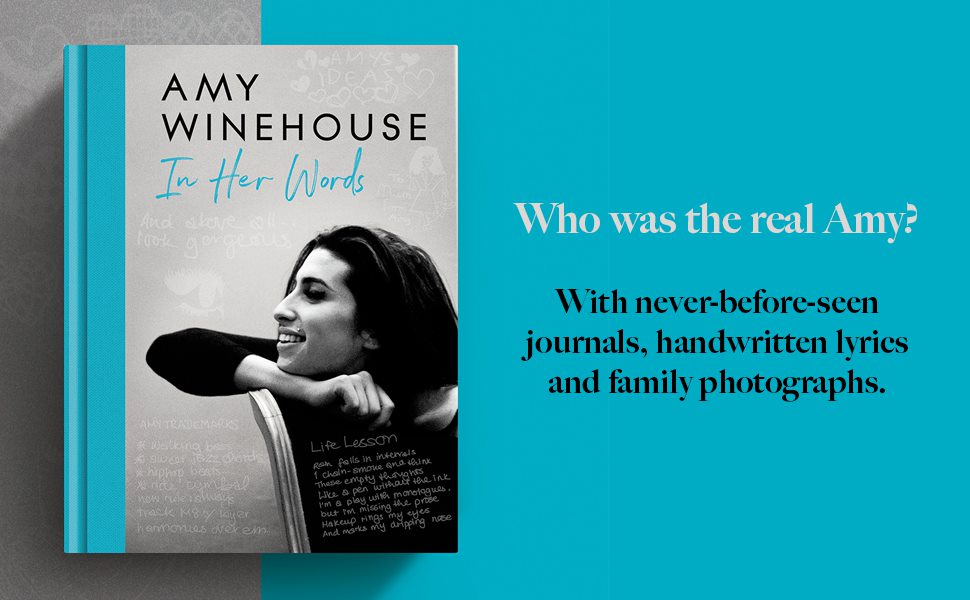

A scrapbook of the late singer’s diary entries, notes, photos, teen poetry and lyrics leans heavily on her early life but offers a vivid snapshot of her personality

Amy Winehouse, 12 years gone, was a perfectionist who hated revisiting the past. She was also a fiercely private artist who closely guarded her process, only revealing songs when she felt they were finished, or as evolved as they could be. We’re told this in the foreword, written by both of her parents, to a generous scrapbook of Winehouse’s personal effects – candid pictures, notes to self, lists, abandoned lyrics, school reports, baby photos – laid out for all the world to see. You can only conclude that one or the other (Mitch Winehouse and Janis Winehouse-Collins split up when Amy was nine) has a very big loft.

It’s impossible to know how Winehouse would have felt about all this, even if the proceeds of this relentlessly touching, often funny coffee table book go to support the charities set up in her name. (At the end there are moving testimonials from two people Amy’s Place, a rehab facility, has helped.)

Her parents reveal that Winehouse accidentally killed her own hamster, they reprint a “mind map” of her school friendships and share her tortured teenage love poetry and the lyrics to a song to a superhero feline called Buff Cat. Some names, such as one on a school-era notebook snippet titled “rating lads”, are redacted.

This is a work heavy on juvenilia and understandably light on the times after Winehouse’s debut album, Frank, was released in 2003. By then, she had been an independent adult for some time, with her own filing system.

Visuals play a big part here. Winehouse often captioned photos of her family, or drew self-portraits with big hair, imagining herself as a “waffle waitress”. Where, say, Kurt Cobain’s Journals compiled vast amounts of written material across the artist’s career arc, this is a book of snatched vignettes rather than correspondence or manifestos – although Winehouse does list “Amy trademarks” circa Frank: “1. walking bass 2. sweet jazz chords 3. hip-hop beats 4. ride cymbal.”

Her diary entries are not what people now call “journalling” – confessional, expository – but crossed-out driving lessons, or when she signed her management contract. The snippets dry up around Winehouse’s powerhouse second album, Back to Black (2006), and beyond, when her life became increasingly complicated. Written in her neat, feminine hand are lyrics to Back to Black’s Tears Dry on Their Own and Love Is a Losing Game, which won an Ivor Novello award in 2008. Then the paper trail ends.

What do we learn? Mostly corroborating evidence. “Good words to describe me: loud, bold, melodramatic,” runs one of Winehouse’s lists. Various teachers reveal that, though bright and creative with a flair for language, she was headstrong and easily bored; she struggled to settle at a number of secondary schools, including Sylvia Young theatre school and the Brit School. “I quickly get into the wrong crowd,” she notes enigmatically, of her time at SYTS.

Little darts to the heart come thick and fast. “Is it worth being bullied for friends,” a younger Winehouse wonders. The older Amy tells herself: “Only smoking after meals. No fucking carbs, bitch!” She later developed bulimia, which contributed to her physical frailty as she battled the addictions that would end her life.

Of all the many images of Winehouse in the wild, her parents chuckle fondly over one in particular: a court artist’s rendition of the singer revealing her lower leg at her 2009 trial for hitting a fan who demanded a photo and wouldn’t take no for an answer (Winehouse was acquitted). This is the caption: “After wrongly being accused of assaulting a dancer, Amy flashed a leg to the judge: ‘Could someone with feet this small be intimidating?’ she asked him. He was lost for words.”