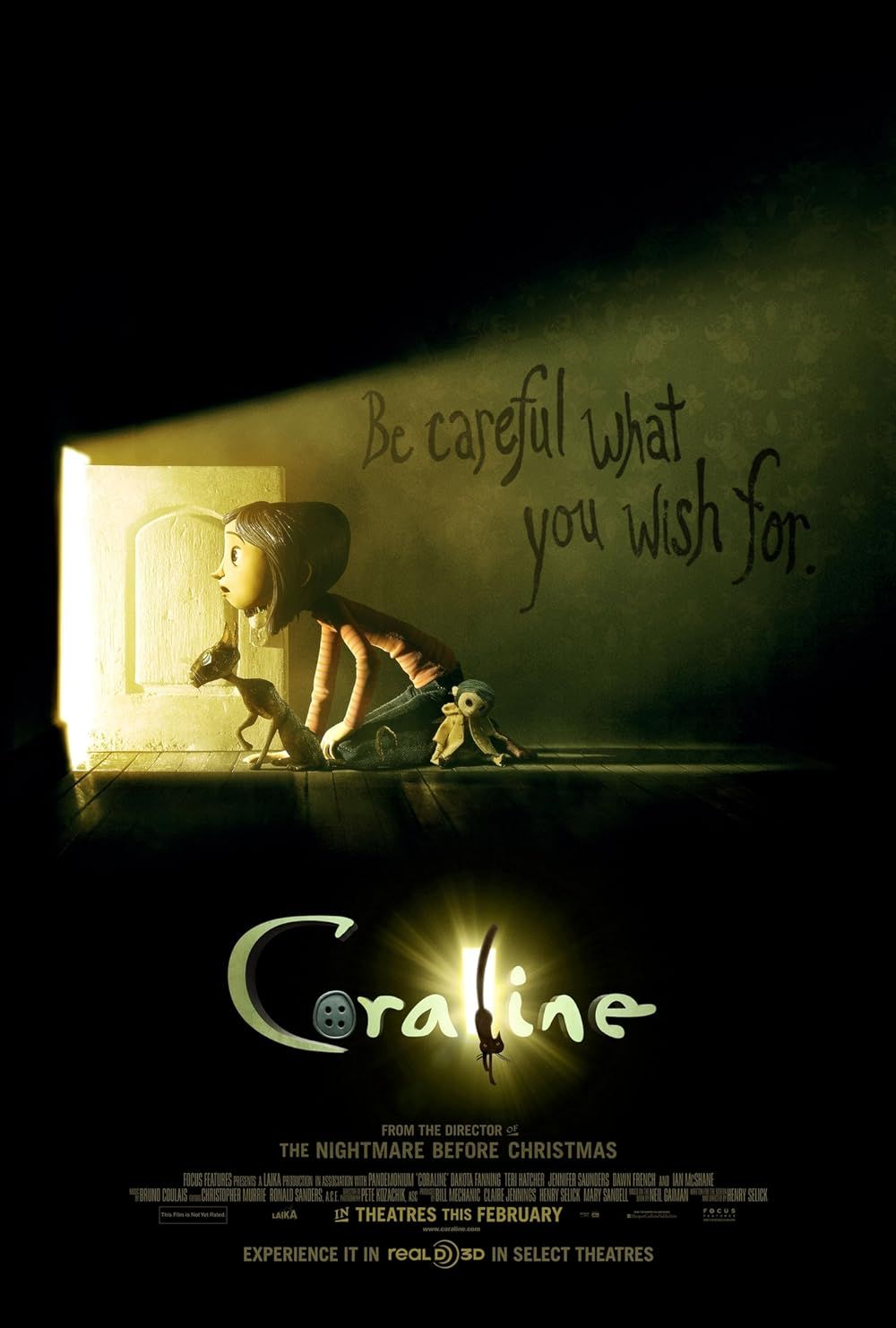

Coraline is a charming adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s book of the same name, but there are crucial differences between the two works of art. Gaiman’s beloved children’s novella Coraline was published in 2002 and quickly became a favorite with readers of all ages. Seven years later, a stop-motion adaptation produced by the now-legendary LAIKA Studios was released under the direction of Henry Selick, the venerated auteur behind hits such as The Nightmare Before Christmas and Wendell & Wild.

Both the Coraline book and the movie are now cherished classics in their own right, with passionate followings that resurface every year when the Halloween season rolls around. A good adaptation does not always mean recreating every aspect of the source material, and the LAIKA movie has some significant differences from Gaiman’s original story. Both the movie and the book are worth checking out, but how is the Coraline movie different from the book?

Updated on May 2, 2024, by Arthur Goyaz: Coraline remains a stop-motion classic that flirts with horror without losing its whimsical tone. The movie is widely accepted as a faithful adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s book, but distinctive elements separate the film from its source material. This article was updated to discuss more differences between Coraline book and movie. In addition, changes were made to meet CBR’s most current standards in formatting.

Coraline Knows Something Is Off from the Get-Go in the Book

Coraline is one of Neil Gaiman’s most beloved properties but these big and small screen projects are perfect for fans who want more of Gaiman’s style.

Gaiman’s Coraline is less than 200 pages long, attending to a standard novella format. In that sense, there’s little time for meandering and the story is quickly set into motion. Different from the movie, Coraline immediately suspects something is off in the book. The Other Mother’s overgenerosity and the enchanting appeal of the Other World seem too good to be true, and Coraline returns only to find her parents have been kidnapped on her first night away.

In the book, Coraline returns home after her first night in the Other World and her parents have disappeared.

In the film, it takes longer for the truth about the Other World to be revealed.

Movie-Coraline is much more naive, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Her desperation to be part of something new enables more worldbuilding. The lingering feeling that something bad is about to happen is beneficial to the film’s tension, effectively setting up the mystery and making Coraline an underrated masterpiece.

Coraline’s Setting Differs Between the Book And Movie Adaptation

Just like most of Gaiman’s books, from The Ocean at the End of the Lane to The Graveyard Book, Coraline’s novella is set in England. As one would expect from a book written by an English writer, the text is infused with British culture. The characters wear macintoshes, eat salt taffy from Bristol, and talk about going down to the shops.

For the movie, director Henry Selick moved the action to Oregon, casting American actors in the majority of the roles. The only holdovers are Misses Spink and Forcible, who are every bit as delightfully British and eccentric as they were in the book. The change of setting doesn’t impact the course of the story, but it certainly takes away some of the book’s identity and reshapes a few of the characters’ distinctive traits.

The Other Mother’s Button-Eyed Rag Doll

Coraline‘s iconic opening is eerie and hypnotic. It features the Other Mother’s spindly, inhuman hands delicately disassembling a voodoo-like rag doll and making it look exactly like Coraline. Not only does it set up the chilling tone of the film but it also introduces an important element that, surprisingly, isn’t in the book.

In the book, the Other Mother doesn’t use button-eyed rag dolls to spy on Coraline. She spies on her targets herself.

In the movie, the button-eyed rag dolls show that the Other Mother has a new target.

In Coraline‘s movie adaptation, the Other Mother makes button-eyed dolls as a way of luring her targets to the Other World. Wybie passes the doll on to Coraline when it shows up on the Pink Palace’s doorstep, and she takes it as a mysterious but adorable gift, making it her companion in her adventures around the house. The dolls turn out to be dark artifacts used by the Other Mother to spy on her targets, but they were invented entirely for the film. In the book, it’s the Other Mother herself who spies on Coraline.

Wybie Only Exists in the Movie

Perhaps the most significant difference between Coraline book and movie is that Coraline’s eccentric companion, Wybie, only exists in the movie. Selick stated that he included Wybie to flesh out the story, as an exact adaptation would only have contained enough material for perhaps a 45-minute film. Most importantly, the main purpose of Wybie’s character is to be a dialogue partner for Coraline, which allows the audience to hear what’s going on in her head, a device that isn’t needed in the written medium.

Wybie, Coraline’s new friend, doesn’t exist in the book.

In the movie, Wybie’s grandmother’s sister is one of the ghosts in the Other World.

Wybie’s existence has some significant impacts on the plot as well — for example, one of the ghost children in the movie is Wybie’s grandma’s sister, who he mentions went missing when they were little. This is the reason why his grandma doesn’t let him go inside the Pink Palace Apartments. The Other Mother also makes a twisted, mute version of Wybie in her world to scare Coraline. Wybie’s presence gives plenty of clues about the Other World’s dark truth in Coraline‘s initial moments, and although he’s exclusive to the movie, the friendship chemistry between Coraline and Wybie is one of the best things about the real-world scenes.

Wybie Plays an Important Role in the Film’s Ending

In the Coraline movie, the ghost children have to warn Coraline about the Beldam’s hand escaping into her world; in the book, she already knows, so she sets a trap for it. Wybie, once again, changes things with his presence, helping Coraline subdue and dispose of the malevolent hand, a feat she accomplishes by herself in the book.

In the book, Coraline sets up a trap to catch the Beldam’s hand.

In the movie, Coraline is saved by Wybie and his motorcycle.

The conflict involving the Baldam’s hand is problematic in both the movie and the book. Coraline is a nearly perfect Neil Gaiman movie adaptation, but Wybie coming out of nowhere to save Coraline at the last minute feels like an upsetting showcase of Deus ex machina. Alternatively, the revelation that Baldam’s hand has escaped into the real world comes to Coraline in a dream, solving the story’s final conflict too easily.

Coraline’s Personality Shifts From Quietly Observant to Feisty

Coraline is overall more polite and pragmatic in the book, whereas she’s quite feisty in the movie. Gaiman writes Coraline as a quietly intelligent and observant child, an echo of other British children’s book protagonists who make it through their adventures with sensible practicality and independence.

In the book, Coraline is practical and sensitive.

In the movie, Coraline is introduced as a reckless loudmouth who goes through great character development.

On the other hand, Dakota Fanning’s portrayal gives a sassier, spunkier take on the character — her version of Coraline is the type of little girl who frequently exclaims, “Ugh!” and calls the unfortunate Wybie things like “Why-Were-You-Born.” Swapping personality traits results in a more reckless main character: Coraline’s naivety makes her more likely to fall for the Other Mother’s ploy, and she only realizes the danger she’s putting her family in once it’s already too late.

The Coraline-Shaped Garden Quickly Became Menacing

One of the enticements the Other Mother sets up for Coraline is the wondrously colorful garden in the yard, which teems with magical flora and is shaped to look like Coraline’s face when viewed aerially. Later, an action-packed showdown with the Other Father takes place in this location, with all the wonderful plants and devices that delighted Coraline so much twisting into their true, terrifying selves.

In the book, the Other Mother prepares a sumptuous meal for Coraline and convinces her to go to bed, but the rats scare Coraline.

In the movie, a lively garden shaped like Coraline’s face is used to lure Coraline.

A lot of the action in the movie takes place in the fascinating garden envisioned by Selick for the film. In one of Coraline‘s creepiest scenes, Coraline crosses the garden only to stumble upon the end of the Other World: a haunting void overwhelmed with white. The Coraline-shaped garden used in the film is a great device used to illustrate the shallow nature of the seemingly lively realm manipulated by the Other Mother: nothing is created in this world, only imitated.

The Other World Is More Enticing in the Film

The Other Mother’s fake world doesn’t really fool Coraline for a minute in the book, but she’s fairly taken with it in the movie. Selick uses his characteristically whimsical visual imagination to create sequences in the Other World that brim over with fun and magic. Viewers themselves might find themselves taken in, which only illustrates how impressive is the worldbuilding featured in the film.

In the book, the Other World is immediately introduced as a suspicious and much darker place than in the film.

The visual representation of the Other World in the movie is whimsical and magical, almost as if trees, plants, and inanimate objects have come to life.

Everything in the Other World reflects Coraline’s wishes: she can have her favorite foods all day long and even has her Other Father sing delightful songs dedicated to her. Everything Coraline wants in the real world is to be seen, and the Other Mother builds a reality where all of Coraline’s most frivolous desires are granted. It’s a great allegory for how children tend to get stuck in their imagination instead of exploring the fascinating world around them — one of the main messages of Gaiman’s story.

Neil Gaiman’s Book is a Lot Darker Than the Film

There are some incredibly captivating and visually impressive stop-motion animated films out there.

Coraline is darker than any conventional children’s movie: the film takes quite a sinister turn once the Other Mother’s true intentions are revealed. From nightmarish sequences to a chilling atmosphere, the movie probably left many kids up at night. It comes as no surprise that Coraline fan theories are much scarier than the movie — there are plenty of disturbing themes to delve into.

The most unsettling scenes in the book include rats singing disturbing songs, shape-shifting monsters, and Coraline’s concerns getting ignored by the authorities in the real world.

In the movie, there’s a dreamlike appeal to the Other World, toning down some of the story’s darkest themes.

However, Gaiman’s book gets even darker. What’s whimsical and dreamlike in the movie tends to be disturbing in the book — the magical glowing tunnel Coraline must cross to reach the Other World is dark and eerie, inhabited by mysterious creatures. The scariest scenes in the Coraline movie are much lighter. In the book, Coraline’s father turns into a dough monster and chases her, the Other Mother bleeds black oil, and most of the eccentric residents of the Pink Palace seem to be hiding horrifying secrets.